From Hexagonal- to Clean Architecture

Introduction to Clean Architecture, comparison with Hexagonal Architecture, and incorporation of Domain-Driven-Design Domain Models.

In some of my latest articles, I moved from a typical Spring Boot application through concern separation and dependency inversion towards a Hexagonal Architecture.

Uncle Bob’s Clean Architecture adds additional rules and nomenclature to the Hexagon. In this article, I want to explore the commonalities and differences and how we can easily move to from Hexagonal to Clean Architecture.

Hexagonal Architecture

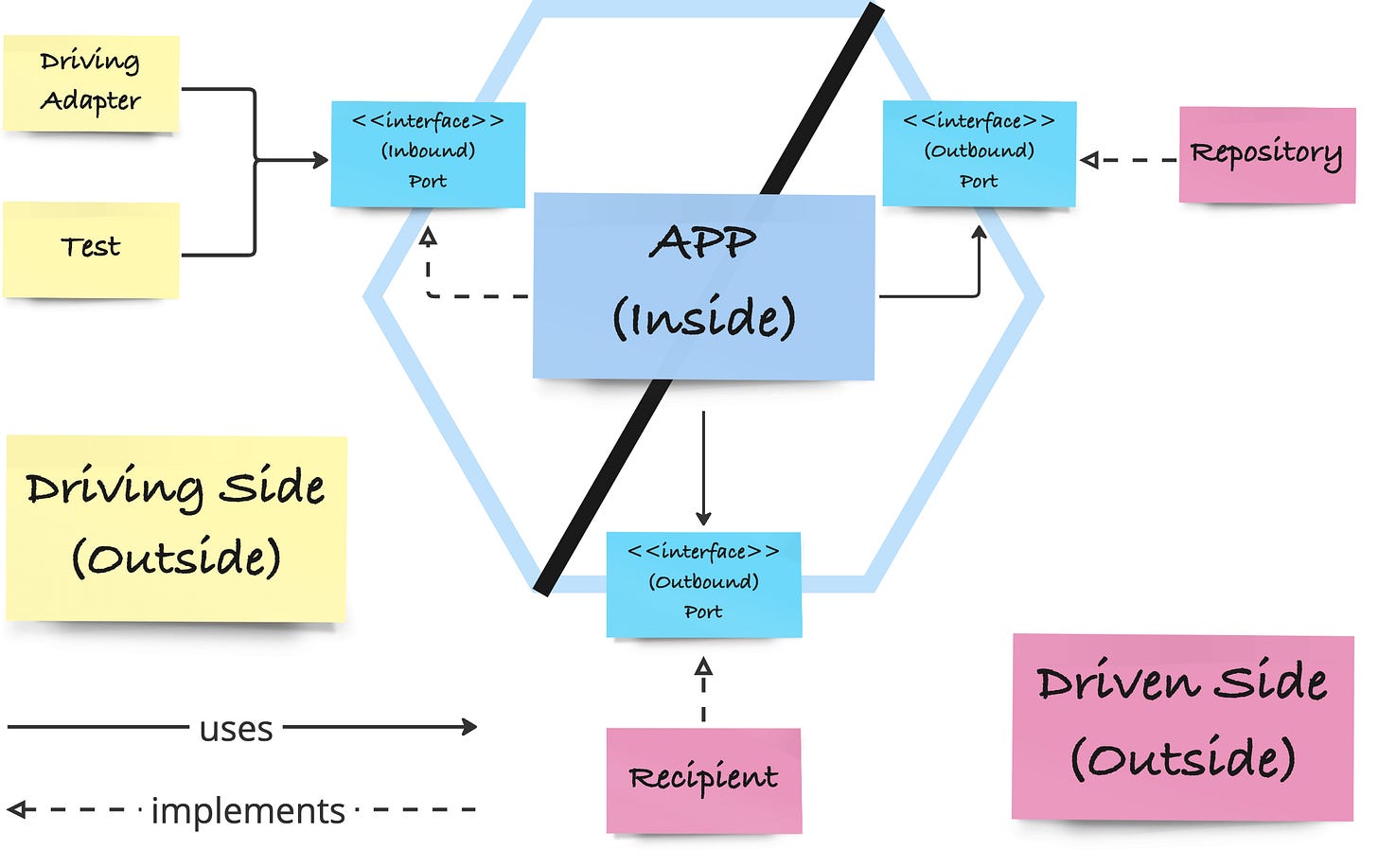

Let’s recap the basic Hexagonal Architecture components:

The hexagon can effectively be divided into outside- and inside components.

The inside of the hexagon contains the actual application. This can be a service method. It communicates with the outside world through ports, which effectively are interfaces that contain either primitive types or types defined within the app. No outside dependencies can be found in the app. It is typically devoid of any framework dependency.

The outside of the hexagon can be divided in driving and driven sides depending on which side of the diagonal they are. Driving adapters use (inbound) ports to map data from an outside source to the internal format of the app, and call (drive) the app through that port. If we practice TDD, the first driving adapter is going to be a test.

On the driven side, we can distinguish between repositories, which are data-access and -storage units to which an application can read to and write from using (outbound) ports. These are bidirectional accesses, so the app can also receive updates from these adapters.

On the other hand, also unidirectional messaging adapters exist that can simply be referred to as recipients. These recipients can be fire-and-forget queues or emails, or also a website that receives the view model.

Importantly, driving adapters use ports to invoke an action on the app, while driven adapters implement the port interfaces and are called by the app through those interfaces. This effectively is a combination of dependency inversion and interface segregation, placing the business app into the center.

From Hexagonal- to Clean Architecture

Clean Architecture builds on Hexagonal Architecture by providing some additional rules and nomenclature to it. The main idea however is exactly the same - separate business concerns from outside presentation- and data-access concerns. It’s a bit like applying certain DDD concepts onto the Hexagon, even though Uncle Bob never really mentions DDD in that context for whatever reason. Let’s see how it compares.

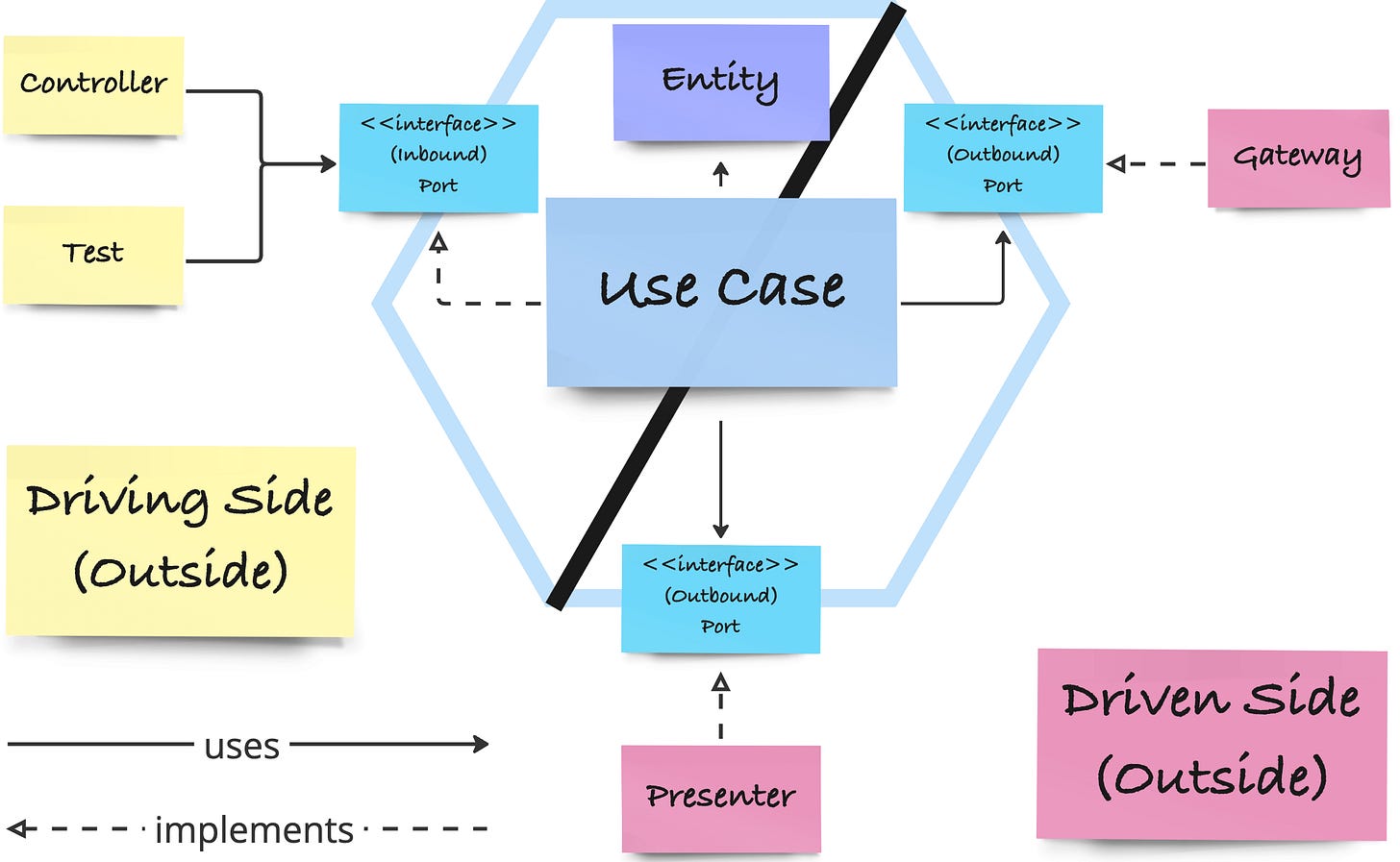

I intentionally kept some of Hexagonal Architecture’s building blocks even though the typical Clean Architecture diagram uses circles to emphasise that if you know how to hexagon, you easily get how to clean:

Use Case instead of “App” or “Inside”

While Hexagonal Architecture stays (intentionally?) vague about the size of the inside of the app, Clean Architecture emphasises a “use case” split. A typical use case could be ReserveParkingSpotUseCaseInteractor or similar business-domain actions, which typically are single application-service methods.

Uncle Bob uses “Interactor” for the implementation names because the inbound port interfaces are named “UseCase”, e.g. ReserveParkingSpotUseCase.

I personally prefer to name single method interfaces as actions, so my interface name would be ReserveParkingSpot, while the actual implementation would be ReserveParkingSpotUseCase. But that’s up to the author of course.

However, the idea of having a set of first-class citizen use cases heavily improves discoverability inside the codebase.

Imagine talking the same Ubiquitous Language as business stakeholders and easily searching and finding these use cases quickly inside the codebase without having to skim through large generic services with many methods.

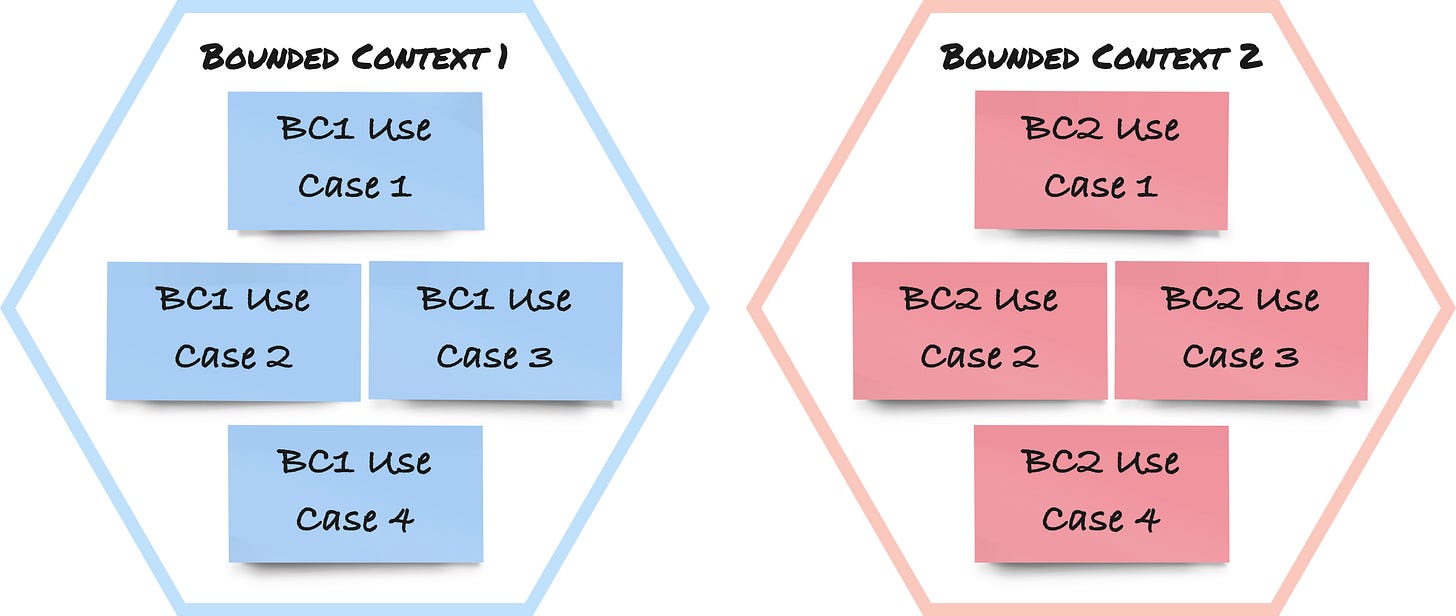

Use Cases also add a great domain-driven granularity to the hexagon, making them perfectly suited to be grouped into DDD bounded contexts as these quotes from Learning Domain-Driven Design by Vlad Khononov imply:

A subdomain resembles a set of interrelated use cases. The use cases are defined by the business domain and the system’s requirements.

Use the rule of thumb […] to find subdomains: identify sets of coherent use cases that operate on the same data and avoid decomposing them into multiple bounded contexts.

Creating Modular Monoliths / Moduliths may be simplified by identifying use case interactors that belong together and grouping them into a single module, effectively creating a starting point for a domain-driven bounded context.

It all seems to come together with the introduction of use case interactors!

Use Cases have the same tasks as DDD’s application services as they are application business rules. In general, they check global validation, load, update, and store entities, and present the result to the outside world through so-called presenters.

Entities

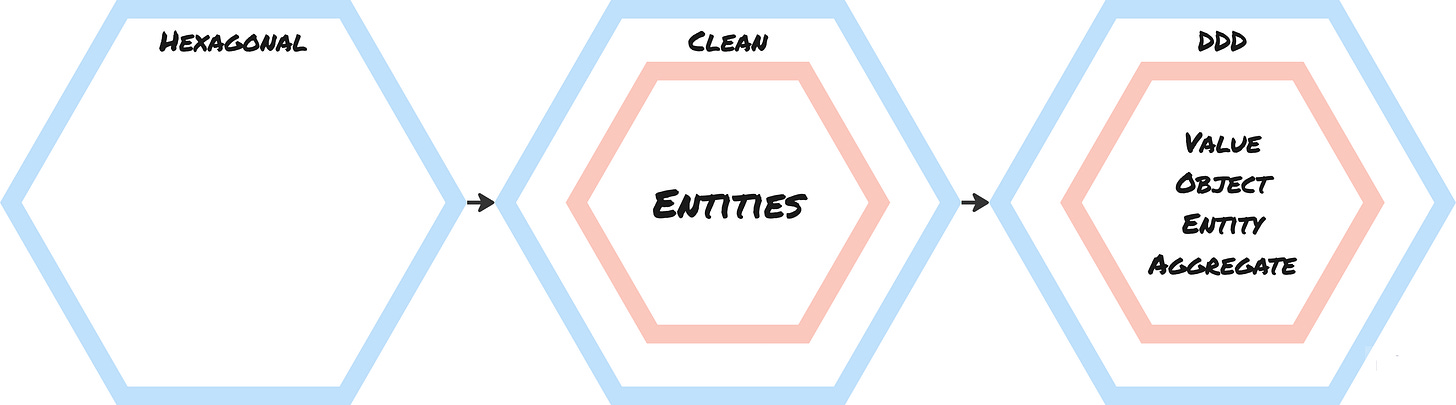

While Hexagonal Architecture does not specify the internal structure, Clean Architecture adds Entities. Entities represent the critical business rules of an application and could be used in a wide variety of use cases across the company.

From that description, they basically fulfil a similar role as value objects and entities of the DDD domain model, but Uncle Bob is less precise about it.

We can see that while Hexagonal Architecture has no definition of how the inside of the hexagon should look like, Clean Architecture at least knows entities. But if you want to be precise with the implementation, then the clearest distinction is to use a DDD domain model as the most internal part of the application, which is also how it is described in Vaughn Vernon’s implementing DDD.

I personally always use a domain folder instead of an entities folder, even when implementing Clean Architecture, and distinguish between entities and value objects even if I don’t use a fully blown Domain Model with aggregates.

Controllers

Taking the name from Model-View-Controller MVC, Controllers act as driving adapters that map the input from some view, like a console or web view, to the format the use case requires, and invoke that use case interface.

Depending on the technology used, Controllers may also be responsible to ensure the output of a use case returned to the view model again. I will show in a follow-up article what I exactly mean by that.

Gateways

While Hexagonal Architecture distinguishes between Repositories and Recipients, Clean Architecture only knows Gateways. However, these ports and their respective implementations have the exact same purpose and therefore can be uni- or bidirectional, depending on what data they transfer.

Presenters

Presenters are specialised ports with respective adapters that do not explicitly exist in the world of Hexagonal Architecture, but could be considered specialised Recipients, meaning unidirectional ports/adapters to the view.

Their purpose is to map between the result of a use case to the respective view model. This means that both success and error cases need to be handled, often leading to at least two ports for presenting them.

The view model created by presenters should be extremely specific. For example, they should specify the color of a button or font to display, such that the frontend simply fills the values from the backend into the required fields. I have yet to see such an implementation in real life, though.

Crossing Boundaries

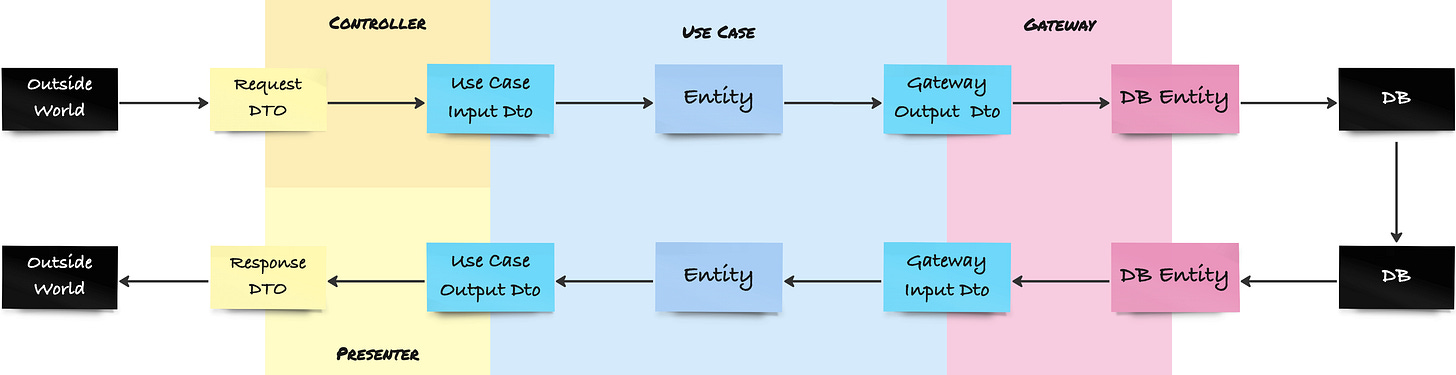

While Hexagonal Architecture does not specify the data that crosses boundaries except that the outside needs to depend on the inside and not the other way round (or be agnostic if primitive types are used), in Clean Architecture, only very simple primitive types, simple data structures like hash maps or DTOs can be used for that purpose.

That means that gateways do not return entities. Entities are built within the use case. Even though I understand the reason behind it, as I described in this article, I typically follow a more pragmatic approach and return DDD aggregates through these data-access ports to reduce the number of mappings as they can significantly slow down the application.

Similarly for the inbound ports, I usually use value objects from the domain model to cross boundaries for the same reason. Clean Architecture would do the mapping and validation inside the use case itself.

Conclusively, if you want to comply 100% with Clean Architecture, you would map a whole lot more between the different concerns than might actually be necessary. It depends on the use case if that is actually really needed, for example if the use case objects should be shared among various teams without exposing their internal structures.

Conclusion

I have discussed the commonalities and differences of Hexagonal- and Clean Architecture.

The main contribution is to split the inside into use case parts. This is a great perspective to build any domain-driven application from, as a couple of use cases together can form a bounded context, which helps modularising applications.

Clean Architecture contains an entity concern at its core, which is a great place to put a DDD domain model into. Such a core is not specified by Hexagonal Architecture.

More specific rules for ports and adapters like Controller, Gateway, and Presenter add additional clarity, but need to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis which make sense and which do not.

Data structures used in ports should be simple - only primitive types, Hash Maps or DTOs should be used. No entities should cross the borders, even for database gateway adapters, which means possibly more mapping between the concerns.

In a next article, I will show how to move from Hexagonal- to Clean Architecture with an example, so subscribe if you don’t want to miss it:

Resources

This article is part of a series moving towards a business-centric architectural design. See the following post to get started.

This series of articles is an addition to the From Layered to Hexagonal Architecture in 2 steps article.

We touch on exactly these topics in our O’Reilly course “DDD, EventStorming, and Clean Architecture”. Check it out to learn how to use Classic TDD to implement DDD Aggregates in Hexagonal and Clean Architecture in one single course.

If you want to learn more about effectively separating concerns, you could also have a look at our on-premise, remote or hybrid workshop Modern Software Architecture Design Patterns. To effectively learn how to identify code smells and refactor them, a core skill needed to transform your application to Hexagonal- or Clean Architecture, also check out our workshop on Clean Code.