Towards Hexagonal Architecture - Folder Structure

I present possible folder structures I used in own projects that capture concern separation, Hexagonal Architecture, and Domain-Driven Design effectively.

When it comes to hexagonal architecture, there are many ways we can structure an application. Some suggestions aim at having one hexagon for the entire app, others separate ports physically from the actual implementation.

In this article, I want to illustrate what works for me and what I have employed in projects already. This means it’s an opinionated article, and others may structure it differently. Take it as a source of inspiration, and then adapt it to your personal needs.

Basic Folder Structure

The basic folder structure of a hexagonal architecture in my projects should always somehow separate the inside from the outside, or the core from the adapters.

Therefore, a perfectly viable, simple structure could be:

app_name

|_outside

|_insideor

app_name

|_adapter

|_coreDepending on the complexity of the application, app_name can represent

the entire application (all the business use cases),

a DDD bounded context (sub-domain-related business use cases),

a single narrow, vertical business-use-case slice,

or any other business-driven decision to split up the application,

as long as the slice represents a vertical, business-driven whole, and not some technical, generic, domain-agnostic concept or horizontal split like “presentation”, “data_access”, “application”, “domain”. The latter splits will find their places inside each vertical business slice, if useful.

Inbound vs. Outbound

If we continue with the “core” vs. “adapter” names, we can also introduce a port folder inside the core which makes it easy to see how we can interact with the application.

An additional useful separation inside the adapter and port folder structures can also be to separate them into “in(bound)” and “out(bound”). That way, we already see that in ports can only be used with in adapters, and out ports with out adapters.

app_name

|_adapter

|_in

|_out

|_core

|_port

|_in

|_outDepending on the kind of adapters employed, it can make sense to add additional information to the adapters that specify what kind of technology they employ. For example, if the inbound adapter is a REST resource, we can add “web” to it. Similarly, when we have in-memory and sql data-access repositories, we can add that to the out folder as well:

app_name

|_adapter

|_in

|_web

|_...

|_out

|_in_memory

|_sql

|_...

|_core

|_port

|_in

|_outDon’t use technology-specific names for port folders! They are inherently technology-agnostic and therefore should not mirror exactly the adapters’ folder structure besides the in/out parts.

Domain-Driven Design Folder Names

Alternatively, or additionally, we can also employ language from Domain-Driven Design in our folder structure.

For example, we can add a presentation folder to the in, and data_access to the out. This can become helpful especially when we add other “out” adapters, for example for sending messages, emails, or other uni-directional recipients that are not direct data access.

The core additionally contains the application, and we could move the ports inside of it, indicating them to be part of the application concern.

Furthermore, if we employ a domain model, we can add an additional folder called domain that can be placed inside the core. I wouldn’t place it inside application however as it represents a separate concern after all.

app_name

|_adapter

|_in

|_presentation

|_web

|_...

|_out

|_data_access

|_in_memory

|_sql

|_...

|_core

|_application

|_port

|_in

|_out

|_domainIn case we need more structure, an additional folder separating values and entities could be added to the domain. Aggregates would become part of that entities folder, or we can add another aggregates folder.

app_name

|_adapter

|_in

|_presentation

|_web

|_...

|_out

|_data_access

|_in_memory

|_sql

|_...

|_core

|_application

|_port

|_in

|_out

|_domain

|_values

|_entitiesThe in- and out folders in the adapter folder, and the core folder may become overly nested here and as an alternative, we could simply have the three main folders adapter, application, and domain inside the app_name.

app_name

|_adapter

|_presentation

|_web

|_...

|_data_access

|_in_memory

|_sql

|_...

|_...

|_application

|_ports

|_in

|_out

|_domain

|_values

|_entitiesAs a consequence, my typical high-level folder structure typically looks like:

app_name

|_adapter

|_presentation

|_data_access

|_application

|_domain and then I add or split as the application grows. I like this structure because it honours separation of concerns, Hexagonal Architecture, and Domain-Driven Design, while avoiding an overly nested structure.

Don’t rack your brain over it. If you don’t need a folder, simply leave it out.

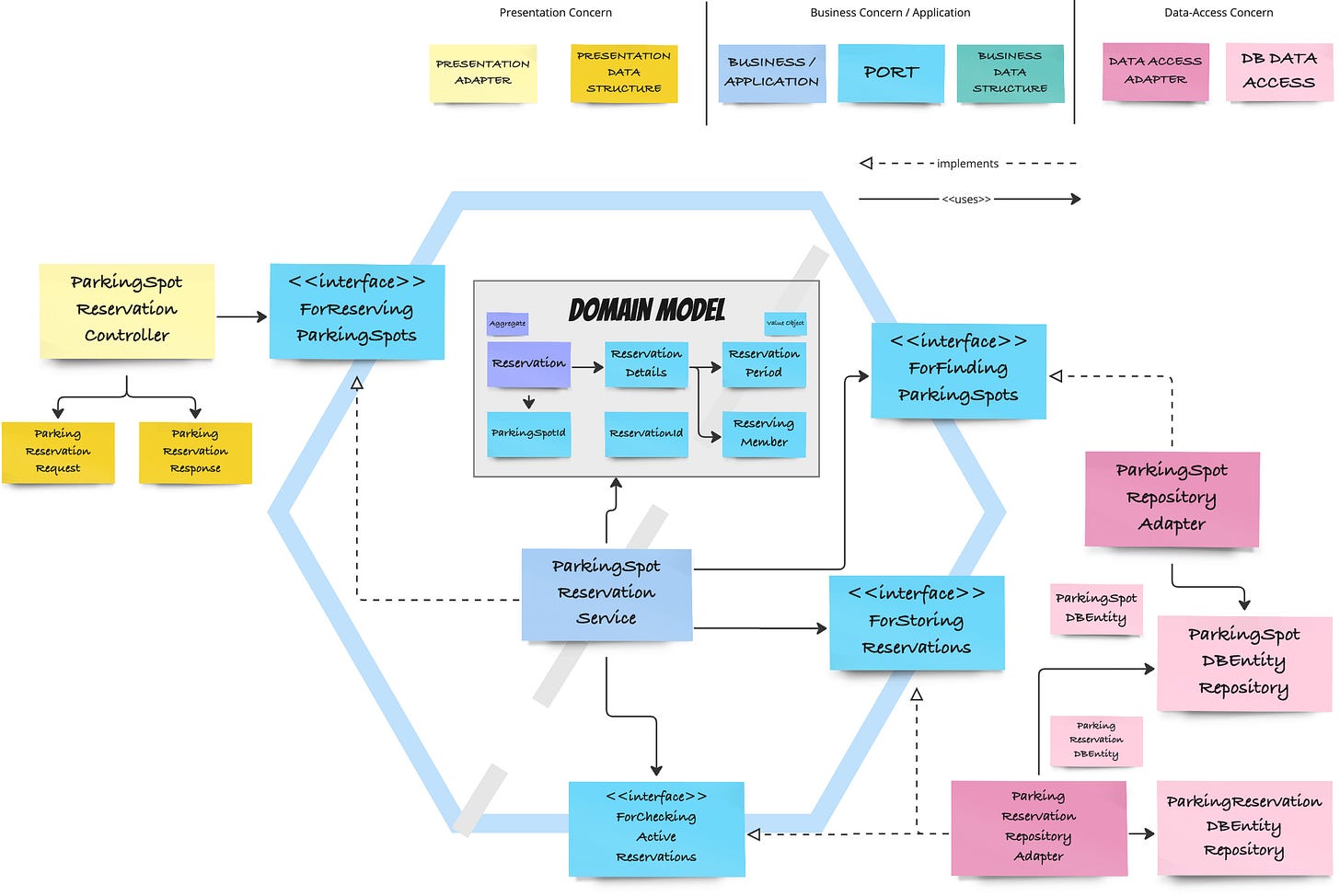

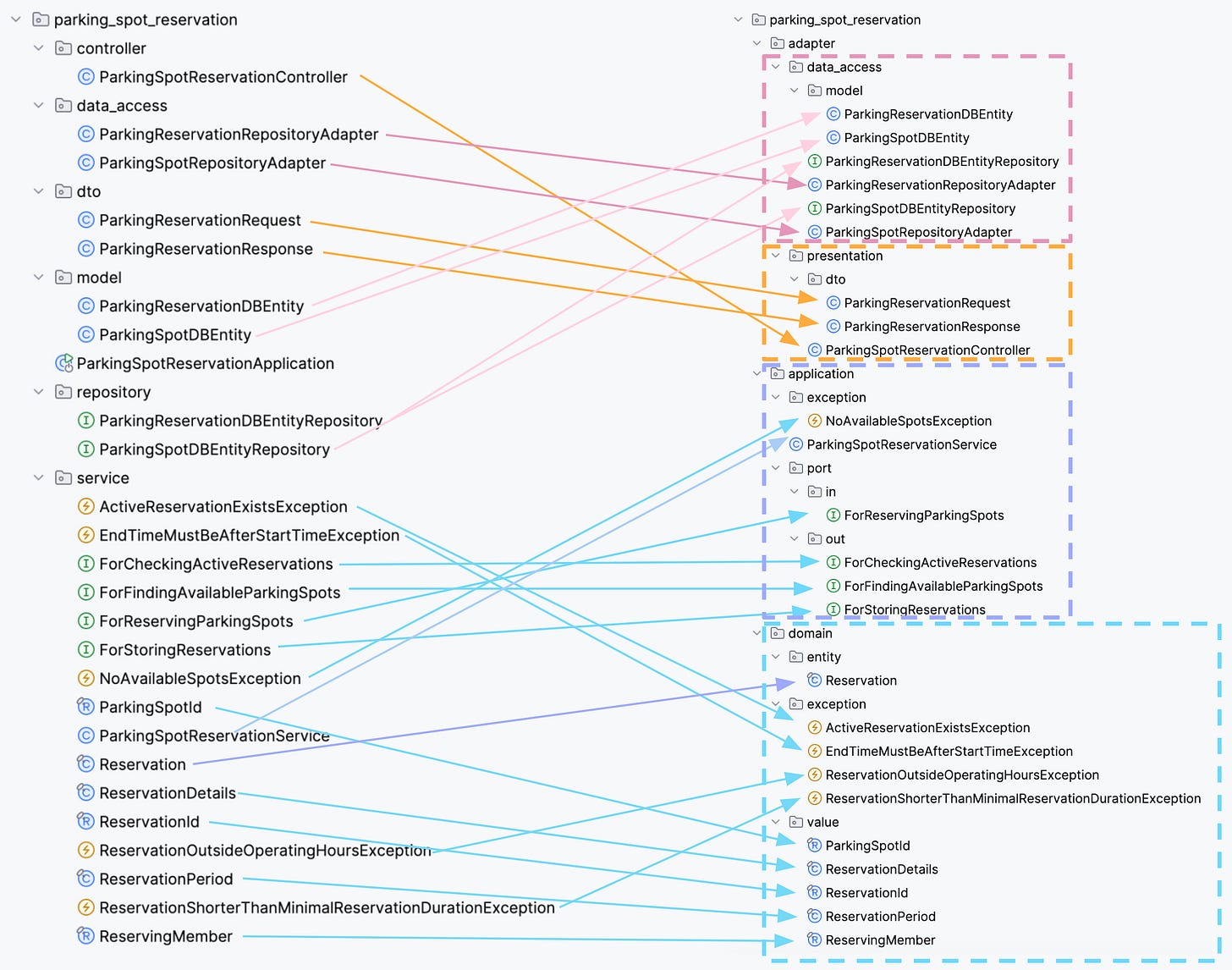

Illustration

The diagram above shows the codebase introduced in the last articles. I left it in an unfinished state regarding its folder structure. This is what I’m going to change now. I choose the following structure:

parking_spot_reservation

|_adapter

|_presentation

|_dto

|_data_access

|_model

|_application

|_exception

|_port

|_in

|_out

|_domain

|_entity

|_exception

|_valueI chose the presentation / data_access / application / domain structure because we immediately find the different concerns and it helps with incorporating domain-driven concepts easily. presentation and data_access are both part of the adapter package.

I take over the dto and model packages from the original structure and add it to the presentation and data_access packages, respectively, but that’s completely optional.

If we work with exceptions, it also makes sense to separate application-specific exceptions, which are thrown only from the service, from those thrown e.g. from a domain value object creation like ReservationDetails. Two additional exception packages in both domain and application folders helps organising them.

I place Reservation, the only possible DDD aggregate in that example, into the entity package. If the application grew without further splitting, an aggregate package may be added as well to highlight the interaction points for the application service, but that would be overkill just now.

The colours indicate the different concerns (red = data_access, orange = presentation, lilac = application, light blue = domain).

You can find the example solution on branch package-structure in the codebase.

It’s important to note that the package structure should be as flat as possible as too much nesting can impede navigation and add more complexity than needed. It is always a tradeoff between more structure and a harder to navigate codebase.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to package structure. Every use case needs to be reevaluated. But the high-level structure of adapter-application-domain, with an additional separation of the adapter package to presentation-data_access, provides a great way to start from.

Conclusions

Different possible package structures exist to organise a Hexagonal Architecture depending on its complexity. A reasonable approach separates inside from outside, or core from adapters.

If we incorporate the 4 different concerns, we additionally add clarity where to put what. The core can be divided into application and domain, the adapters get two additional packages presentation and data_access.

The highest level folder can be the entire application or smaller bounded contexts or even use cases. It always depends on the complexity of the application.

We need to avoid overly complex nested structures as these can hinder quick navigation. It is always a trade-off between more structure and easier access.

Resources

This article is part of a series moving towards a business-centric architectural design. See the following post to get started.

This series of articles is an addition to the From Layered to Hexagonal Architecture in 2 steps article.

We touch on the same topics in our O’Reilly course “DDD, EventStorming, and Clean Architecture”. Check it out to learn how to use Classic TDD to implement DDD Aggregates in Hexagonal and Clean Architecture.

If you want to learn more about effectively separating concerns, you could also have a look at our on-premise, remote or hybrid workshop Modern Software Architecture Design Patterns.

To effectively learn how to identify code smells and refactor them, check out our workshop on Clean Code.